After the murder of Sarah Everard in London, countless women around the globe took to social media to speak out about the harassment, fear and panic they face when walking home alone at night, faced with the uncertainty of not knowing what threats or dangers they might encounter. Yet many people blamed the victim. Behind this lies the deeply rooted human belief in a just world.

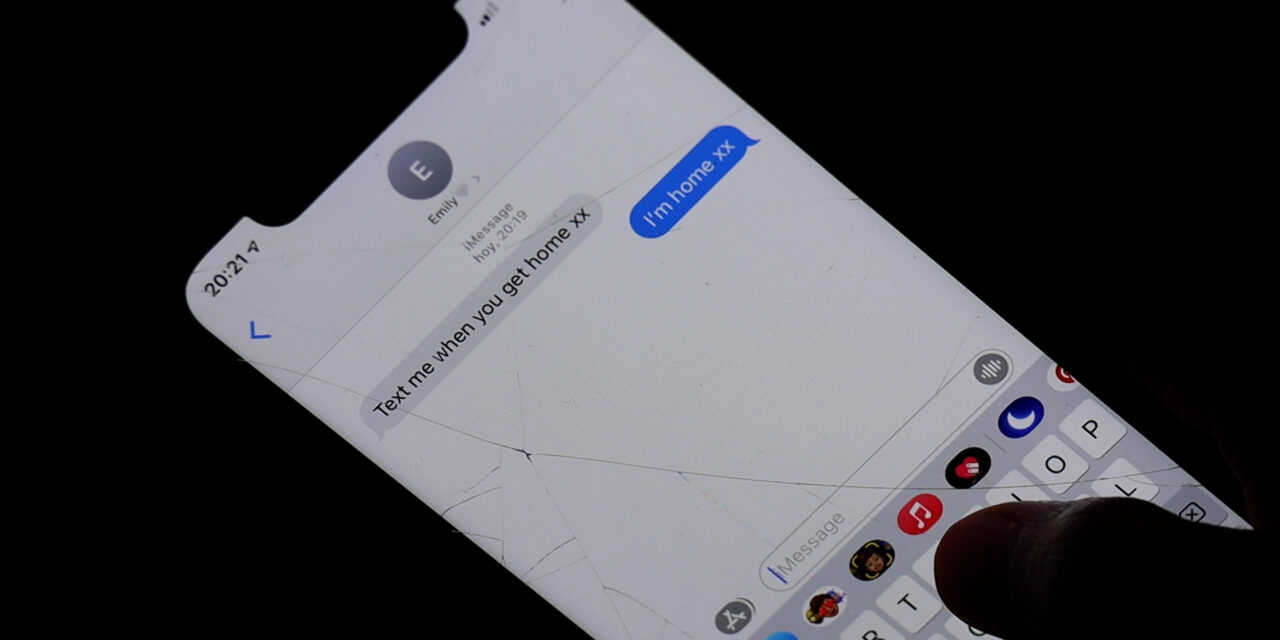

It’s Friday night. After dinner with your friends, you walk home alone. With the hood pulled over your head and the front door key clamped tightly between your fingers, you constantly turn around in all directions to make sure that no one is following you. Every sound of footsteps, every flash of car lights makes you hold your breath for a moment. You fake a call on your mobile phone to give the impression that you’re not alone. Finally, your house looms in the distance. You pick up your legs and run the last few metres before throwing yourself exhausted on your bed and writing a message to your friends: “I’m home.”

For the vast majority of women, such situations are part of everyday life and they don’t always end well. According to a UN survey, 97% of women in the UK aged 18-24 have experienced sexual harassment in public spaces. When 33-year-old Sarah Everard disappeared on her way home in London in early March and was found murdered a week later, a debate about pervasive violence against women erupted on social media. Countless shared their experiences of sexual assault in public and what they’ve felt forced to do over the years to ensure their own safety on the streets. The internet once again experienced a #MeToo moment.

Sarah did everything “right”: she wore trainers and light-coloured clothes, walked on well-lit streets and talked to her boyfriend on the phone. But even that did not stop many from blaming the victim. Voices were raised on Twitter asking, “Why was she out alone at 9:30 pm? Was she drunk?” In a 2016 survey by the European Commission, 27% of EU citizens said that rape was justified in some cases, such as when the woman was dressed too revealingly.

This type of reaction, evaluating a victim negatively because of what happened to them, has been well studied in psychology and is not only applicable to sexual violence. Michèlle Bal, assistant professor in Interdisciplinary Social Science at Utrecht University, explains: “Every time we’re confronted with something that we consider unjust, happening to someone else, we can see these types of responses. A strand of research investigates how people react to people who fall ill.” However, victim blaming occurs most frequently after sexual offences, she adds.

As early as the 1980s, social psychologist Melvin J. Lerner developed the just-world hypothesis to explain this phenomenon. According to Bal, the reasoning goes like this: “People care about living in a world that’s just and that’s fair because only then does the world become predictable, and they can trust that if they put effort into something, it’ll pay off in the end. If they’re confronted with injustice, this belief becomes threatened.” The first step in trying to resolve this threat would be to help the victim, which is not always possible, especially if confronted through the news. Victim blaming provides an alternative: “If you’re able to blame the victim for their victimisation, then it’s no longer unjust and thereby you can still have faith that the world in general is just.”

Through experiments, Bal has found that men engage in victim blaming more explicitly, therefore stating one is to blame, but when it comes to more implicit forms, like assuming a victim was drunk, the gender difference disappears. A number of other factors play a role, such as the extent of the threat: “For example, if the perpetrator is caught, then justice will be served and it’s a lower just-world threat than if the perpetrator is still at large.” Accordingly, one is also more tempted to blame the victim if the offence occurred nearby or if the victim is similar to oneself.

Such a form of secondary victimisation can have serious consequences, both for the victim and for society as a whole. Mental health issues aside, victim blaming creates an environment in which sexual assault is normalised – a so-called rape culture. Speaking out becomes less likely for fear of not being taken seriously and perpetrators are ultimately not held accountable. Various studies suggest that only 15% of sexual assaults are reported to the police.

So, what needs to happen for people to offer their support? According to Bal, it is necessary to divert the attention from the threat to the victim. “If you’re not focusing on what it means to you, that you are confronted with this victimisation, but you’re more focused on how it must feel for the victim to be in that situation, then you’re much more likely to give an empathetic reaction.” Social networks add a whole new dimension to the problem: “Online blaming is much easier because you can do it anonymously and you don’t see the person you are blaming.”

But it was also the social networks where countless women shared their personal stories in the course of #MeToo and gave sexual violence a face. Anonymous victims became human beings to care about. In the weeks following Sarah Everard’s death, a text board was shared particularly frequently, with the phrase “Protect your daughter!” crossed out and replaced with “Educate your son!”. It points out that sexual violence is never the victim’s fault and that it should not be the responsibility of women to protect themselves from such.

When #notallmen subsequently trended on Twitter, actress and activist Jameela Jamil wrote: “It’s true that #notallmen harm women. But do all men work to make sure their fellow men do not harm women? Do they interrupt troubling language and behavior in others? Do they have conversations about women’s safety/consent with their sons? Are #allmen interested in our safety?“ The same applies to victim blaming.

In the following video, three female students from three different parts of Europe share their own experience with sexual harassment in public, tactics they have adopted to protect themselves from such and what they would want society to do instead.

[embed]https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uVVhXfhtous[/embed]