Slavery is more than just a painful memory in the United Kingdom. As an unhealed wound, the legacies of the country’s involvement in the trade of human beings can still be seen today. And amongst all the cities that thrived and profited from the slave trade, there was no British city to rival Liverpool, as the city became one of the world’s capitals of this horrendous business.

To better understand the importance of Liverpool in the global slave trade, picture yourself as an enslaved person from Africa being brought to the Americas by the British. According to the BBC, the chances that you would have been shipped across the Atlantic by a Liverpool-based vessel were six in ten during the 18th century, with Liverpool controlling around 40% of the entire European slave trade during the period.

This kind of heritage, if not tackled fiercely, can bring up a series of nasty consequences to society. The racist mentality, which motivated the slave trade in the past, is not at all gone for good, and can still take many shapes and forms. Two manifestations of this inherited prejudice are hate crime and structural racism.

Hate Crime

“The report of hate crime is getting worse every year, and this tendency is being replicated in Liverpool”, says Clifton John Williams, Operating Officer at the Anthony Walker Foundation in Liverpool.

The Anthony Walker Foundation was founded after the racially motivated murder of Anthony Walker – an 18-year-old man whose skull got perforated by an ice axe during a walk with his girlfriend – and is responsible for assisting victims of hate crime, as well as developing educational initiatives in the region of Merseyside.

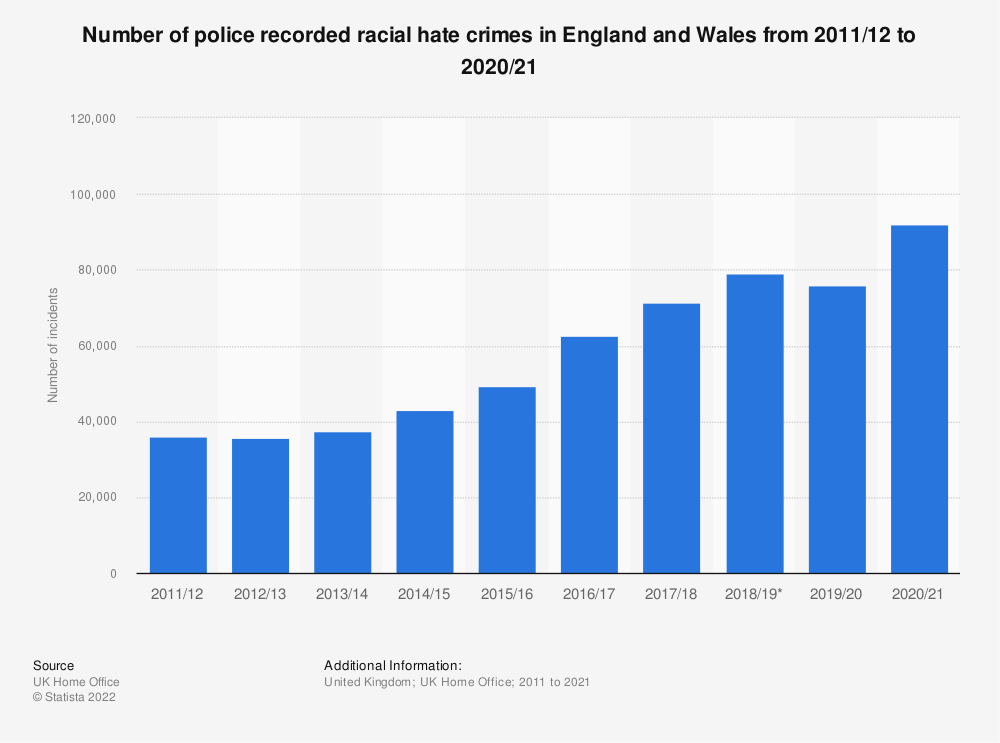

Indeed, as the graph below by the UK Home Office shows, the number of racial hate crimes has been increasing year after year:

To explain this phenomenon, apart from the racist heritage, Mr Williams says that other more recent aggravation factors must be taken into consideration: “During the Euro 2020 final, three black players missed penalties which cost England the championship, exacerbating the situation, and increasing the targeting of people of colour. Other factors are Brexit, the ‘Trump effect’ – the American President’s rhetoric stimulated xenophobia and racism – and the murder of George Floyd along with the #BlackLivesMatter wave of protests, which sadly stimulated even more racist targeting.”

“The covid pandemic was also an aggravation factor, as people had to operate in close proximity due to the lockdown. During this period we saw an increase in neighbour dispute and a number of prejudice cases”, adds Mr Williams.

Mr Williams comments he is tempted to believe that this increase in hate crime reports may be due to people feeling more confident about speaking out, but this might be an overoptimistic approach, and it cannot be denied that hate crime is on a rise.

“And we must stop it. Anthony Walker and George Floyd paid the ultimate price, with their lives. We must stop it, before another person falls victim of hate crime.”

Structural Racism

The city of Liverpool is not uniform. To this day, there is still a sort of a racial division in the city, with certain parts of the south of Liverpool being diverse, whilst most of the north having a white majority, which, according to sociologist Dr Amina Elmi from the University of Liverpool, leads to “racism being still entrenched in this part of the city”.

But such division is not new. “The division between white and black has always been prevalent and dates to Liverpool being a slave trade city, as the economic growth of the city was dependant of the exploitation of a certain race”, says Dr Elmi.

“Liverpool is a city divided, as those who live in the North of the city do not interact with those who live in the south.”

The local political sphere is also partially responsible for the perpetuation of such structural racism, with voters normally failing to critically assess their political candidates and not prioritising the real issues, as explained by Dr Elmi: “Liverpool when it comes to politics is a one-party city, with Labour being the party in control for large time periods, and this means the city lacks competition. If competition existed, then parties would vie for votes and tackle issues which affect certain populations, but as the city is mainly a one-party city, the party in power does not have to address racism or hate crimes, as their votes are secured.”

“People in Liverpool do not vote for a certain party tackling/eradicating an issue, but they vote based on party identity.”

The structural racism in Liverpool is also seen in other ways, as John Williams points out: “We have got to remember, it is not by accident that there are more black people living in the most deprived areas of Liverpool, it is not by accident that there still a huge wealth disparity based in race, etc.”

All these problems and racial issues are the outcomes of a heritage people in the city are struggling to face, “It’s a legacy that Liverpool has never recovered from, and one that is very much apparent today. It can be seen in the institutional racism that exists for the Black community in all avenues of employment, education, health, social care, etc”, says Dr Elmi.

A glimpse into the future

But there is still hope. The city of Liverpool is starting to gradually acknowledge its past. It began in 1999, when Councillor Myrna Juarez proposed to Liverpool City Council the debate of a motion to ‘express remorse for the effects of the slave trade on millions of people worldwide’. This motion was approved and led the City Council to officially acknowledge Liverpool’s involvement in the slave trade and formally apologise, establishing a milestone and starting to spark the debate on the city’s historical background.

Dr Elmi also points out another recent political factor that is contributing to more developments in this delicate field: “Liverpool elected its first Black mayor in the last elections, and she has changed the optics of the city, placing hate crime and racism at the forefront of the city’s agenda.”

The only way of solving these issues related to race is by giving them the importance they deserve and acknowledging the reasons behind it, which, in Liverpool’s case, are very much intertwined with its involvement in the slave trade.

Because, as Mr Williams concludes: “People do not become racist overnight.”

Mr Williams further comments on Liverpool’s racial situation and the work of the Anthony Walker Foundation can be heard in the podcast “Racism & Slavery in Liverpool”: