Walking through the old streets of Ljubljana, one is immediately absorbed by the romantic, culturally charged atmosphere of the city. Peeking into the café terraces or one of the numerous parks of the city, one can spot its people with a book in their hands, occasionally keeping an eye out for wandering tourists.

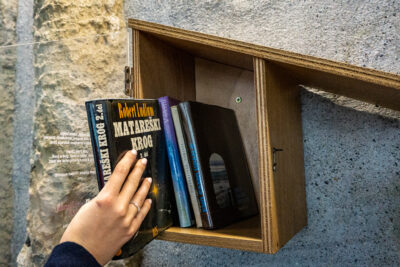

Books and literature can be found everywhere in Ljubljana: If you look close enough, you can discover small bookshelves spread out in every corner of the city, accessible to everyone. And if it gets a bit crowded on the bus on the way to work, don’t worry – a seat for reading is reserved. With a public book network with over 500,000 members and numerous literary events, Slovenia, and more specifically Ljubljana, seems to understand a lot about literature. The city of Ljubljana is UNESCO World Book Capital, UNESCO Creative City of Literature and hosted the first World Book Summit. Of course, that brings a lot of tourism every year. But in Ljubljana, even the people seem to breathe and live literature.

“Creativity is considered an important value in Ljubljana,” explains Alenka Žbogar. She studied Slovenian and comparative literature and is now teaching future Slovenian professors at the University of Ljubljana. Her passion for literature comes from her childhood, as it does for many Slovenes. “Personally, literature and the desire to teach have accompanied me for as long as I can remember.” Therefore, she sees the importance of reading as a cultural asset. “Reading internalizes the awareness that literature is a cultural asset and part of cultural heritage. Through literature, language, and culture, we Slovenians have affirmed ourselves as a nation.” Slovenia received its first printed book in 1550, and the Bible was first translated into the language as early as 1584. This makes the small country of Slovenia the fourteenth nation in the world to receive “the book of all books” in their native language. “We’re one of the few nations that celebrate a culture day as a national holiday. On that day we commemorate France Prešeren, the poet that raised Slovenian literature to a European level in the 1830s,” the professor describes the direct connection between culture and literature.

Drifting through the scenic streets of Ljubljana, one will find a bookshop on almost every corner. If you’re looking for something old and unique, the Trubarjev Antikvariat is the place to go. The oldest bookshop for second-hand and rare books is located in a small, almost hidden alley opposite City Hall Square. In contrast to the many old books that immediately catch the eye when you enter the bookshop, 27-year-old Ruby Knap can be found behind the sales counter. Through her work, she too experiences the Slovenes’ special connection to the literature daily. “Books and literature are really everywhere. We have a tremendous amount of bookstores, secondhand bookstores, concentrated in such a small space.” Their customers couldn’t be more diverse, she explains: “Anyone from tourists, to students that need some school materials or somebody who’s just looking for a book which is currently sold out. But also bibliophiles, collectors and even institutions like libraries and museums are part of our clientele.” If you ask Ruby about the competition from other bookshops, which is obvious to visitors, she cannot help but grin at first. “Everybody always wonders, how do you even survive this close to each other? Do you have enough business to survive? And yes, we do. Apparently, people in Ljubljana, really do love reading.”

It seems no surprise that Ljubljana, holding the title of UNESCO Creative City of Literature, attracts a lot of creative minds and thinkers. According to Nataša Čebular from the Slovenes Writers’ Association, “the concentration of many literary institutions and literary workers creates more possibilities for financial aid for literary projects and makes Ljubljana a city of literature. The city has an infrastructure that ensures diversity within the literary scene is possible.” However, continuous work is needed to ensure this diversity. “There is a tendency of many regional and national governmental institutions towards a monoculture, also in literature. This means the non-commercial and underground literary scene is being pushed to the border of the city,” she further explains.

In the eyes of Slovenian poet, translator and literary critic Barbara Pogačnik, the young and creative literary sector tends to move away from the many events hosted by municipalities under the title of UNESCO World City of Literature. Above all, she sees a problem in the replacement of traditional events with new ones. “It all gets a little bit pushed aside because of the activities of the municipality and what they do to have this title. I will say that I’m a little bit sceptical about the way that is being implemented.” After all, the writer hopes that the change of government last year will lead to more financial support for freelance writers and honorary workers.