The Roma people are a historically socially marginalized minority in Europe. Roma rights groups have been trying to change this since the 1970s in various ways, through education, representation, storytelling and the visual art medium. Roma artists use the visual art medium to recontextualization of what it means to be Roma, while also dealing with the trauma inflicted upon their people through history. How does this look in a modern society? And how does contemporary Roma artist develop a visual artistic language, when there historically hasn’t been one?

Text and Illustrations by Mathias Krogsøe

Photos and videos by Jester van Schuylenburch

The cultural landscape is changing faster than ever, thanks to new technologies and increased globalization, all over Europe and the rest of the Western world. Simultaneously, change in how we treat and talk about minority groups are fast evolving. In academics, civil society, and on the governmental level. Minorities are now more vocal than ever, partly due to the new technologies, and the use of social media.

The Roma community has long been stigmatized, prosecuted, harassed, and even executed because of their heritage and lifestyle. Most prominently during the genocide of Roma people, by the Nazi regime in the 1930s and 40s, during the Holocaust. All of this is deep-rooted in their history and sense of identity. Something contemporary artist today are trying to deal with through their artworks and something non-governmental organizations are trying to vocalize and educate the people of the world about.

Stigmatization and racism still follow the Roma community to this day. And negative stereotypes like the Roma being dirty, liars and thieves still prompt governments all over Europe to ban Roma camps. An example of this can be seen in the Scandinavian country Denmark. In 2018 the government issued a law prohibiting congregations of more than 50 Roma people in one place on the grounds of a presumed rise in petty crimes in the areas.

Sign from 1964 that means no “gypsy” people In Poland

More recently, multiple media outlets, including The New York Times and Al Jazeera, have reported on the discrimination Roma people experience when trying to flee war-torn Ukraine. Many reports tell of people being denied access to cross the borders surrounding it, especially in Moldova, only because they are Roma and the stereotypes that follow. Until the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the country had one of the largest Roma populations in Europe.

Contemporary Roma artists seek to fight this discrimination and the negative stereotypes with positive representation and recontextualization of what it means to be Roma. In cooperation with Roma culture organizations who are now bigger than ever and are increasingly providing a spotlight on Roma artists, culture and issues, they seek to change how the world looks at Roma and how the Roma look at themselves.

Using positive stereo types & confronting negative stereotypes

In Tarnów, Poland, at the Muzeum Etnograficzne w Tarnowie (Ethnographic Museum Tarnów), resides the only permanent exhibition of its kind in the world, presenting the history and culture of the Roma people in the context of their European heritage. According to the former director and creator of the museum, ethnographer Adam Bartosz, the exhibition seeks to confront and change the stereotypes of the Roma people, as well as use the positive stereotypes like freedom and liberty, to promote the culture. The Museum does this through artifacts and curative storytelling as well as exhibiting contemporary Roma artworks by Polish Roma visual artists such as Krzysztof Gil and Małgorzata Mirga-Tas. The director explains this is to show the Roma past and possibly the future through contemporary art. Visual art is a relatively new thing in the Roma community, where oral storytelling, music, and dance historically was the main ways of artistic expression. Adam Bartosz:

“Until very recently in history, The Roma didn’t have so much visual art, they had no tradition for it. But since the 60’s and 70’s Roma artist have tried to develop a visual art language of what Roma art could be and what it is now.”

The artworks by Malgorzata Mirga-tas displayed at the Muzeum Etnograficzne w Tarnowie

Małgorzata Mirga-Tas does this very deliberately. The New York Times described her as “The Roma artist sewing a new history for her people” in February this year. She works with many mediums like sculpting, painting, and printing but is best known for her sewn “paintings.” Her artworks often depict everyday scenarios featuring Roma people, made with vibrant fabrics and referential patterns from traditional Roma clothing and decorative style, as seen on the Caravans for example, which the Roma are known for.

The open-air backyard of the Muzeum Etnograficzne w Tarnowie is home to several original Roma Caravans recreations that were either bought by or gifted to the museum over the years since it opened.

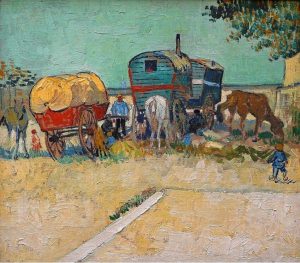

Mirga-Tas does something central for many contemporary Roma artists in their artwork; presenting imagery of Roma from the inside perspective, that of being of Roma descent, rather than from the outside perspective as it has historically been the norm when it comes to depictions of the Roma and their lifestyle. One of the more famous examples is the oil painting “Gypsy Camp near Arles” (1888) by Dutch painter Vincent Van Gogh.

(The oil painting “Gypsy Camp near Arles” (1888), courtesy of www.VincentVanGogh.Org. In recent years the word “Gipsy” (or Gypsy) has been seen as increasingly offensive due to its racist and negative usage through the ages. People and governments have opted for the terms Roma or Romani when referring to the minority. This change has been a wish of the minority since the first “World Romani Congress” in 1971, where the attendees unanimously voted to reject the use of the word “Gipsy”. Some Roma still use the word today in some contexts, for example when talking about “Gipsy” history.

Representation through memory One of the organizations working to increase positive representation is RomArchive, an online digital database focusing on self-representation. The project was initiated in 2015 by activist and scholars Franziska Sauerbrey and Isabel Raabe, who both have Roma heritage.

Since then, the platform has grown and is now run by a multinational team of curators, mainly of Roma descent, fighting to pass on knowledge about Roma culture and counter stereotypes by providing an abundance of information on Roma art and artist in carefully curated sections such as Visual art, Theatre, Dance and the Roma Civil rights movement.

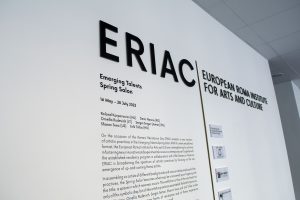

The first and only institute of Roma art

The European Roma Institute for Arts and Culture, ERIAC for short, is another organization that strives to reduce stigmatization and increase positive representation. ERIAC describes itself as a central international cultural hub, promoting activities of Roma organizations, intellectuals, and artists “to form multilateral initiatives and regional alliances and connect them with the policymakers and leaders of the different national and European levels. ERIAC does this in a myriad of ways, through helping people make connections, lobbying for Roma rights groups, and through exhibitions and events featuring Roma Artists and cultural front runners.

“ERIAC exists to increase the self-esteem of Roma and to decrease negative prejudice of the majority population towards the Roma by means of arts, culture, history, and media.”, says project coordinator Joanna Wojtarowicz.

ERIAC is financed primarily through EU funds and the German government, as its headquarters is in Berlin, Germany. The Serbian government also provides funding for the Serbian branch of the institute located in Belgrade. The funding by national governments and from the EU also shows the added focus on promoting these cultural institutions. Plans for branches in more countries as the organization grows are in the works but still in the planning phase.

outside of ERIAC Berlin

A long history of prosecution

Around the year 1000CE, a nomadic people, now referred to as the Roma or Romani people, began their first wave of emigration westward from their ancestral homelands in the east, mainly from areas of what we now call India. Multiple Roma waves have travelled towards the European continent since then across the centuries. The Roma people spread out all over the continent and into many different subgroups and clans or “families” with their own kings and queens between them. Today, the word Roma or Romani is used as an umbrella term to cover all these different subgroups by governments, media, and the people themselves.

The Roma is a nomadic folk, never settling in one place too long, until very recently, in a historical sense, crossing borders and cultures along the way; one of the reasons historians and ethnographers have a hard time precisely pinpointing the Romani down to one specific thing. They are a mix of everything they picked up along the way. In Italy, they picked off their somewhat matriarchal family structure; in the Balkans, they found their musical instruments and signature sound. Another good example is the “Roma cuisine,” which highlights their greatly mixed cultural heritage. Mediterranean influences and spices, and the fermented foods of German and Poland in particular, like sauerkraut for example, mixed in with other Balkan staples such as goulash and stews. Hedgehog goulash is widely regarded as a delicatesse and the unofficial “national dish” of the Roma people. A truly culturally mixed people.

Since the Roma people arrived in Europe, they have been marginalized and persecuted due to their low social status, nomadic lifestyle and “exotic appearance”, making them seen as lesser than others and as somebody who could be harassed, enslaved, and executed without consequence. As early as 1300-1400s, European states passed laws declaring the Roma lawless or enslaved people by default if they entered their territories.

Historians and ethnographers, like Adam Bartosz of Muzeum Etnograficzne w Tarnowie, believe this racism and suspicion that followed the Roma into Europe stem from the fact that the Roma arrived in Europe around the same time as the Mongols, invaders from the east. This association and later that of other eastern invaders, the Ottoman Empire, due to the Romas’s “exotic lifestyle” and darker skin, caused persecution in Western Europe and, in some cases, led to ethnic cleansing of the Roma people.

The historical peak of this happened in Germany in the 1930s and 40s during the Romani Holocaust, called “The Porajmos,” in Romani meaning “the devouring.” From 1935-45 an estimated number of between 220.000-550.000 Romani and Sinti (a subgroup of Romani people primarily found in Germany) were executed in concentration camps, along with everyone else Nazi Germany didn’t see fit to be a part of their Aryan Third Reich. Because there was no official registration of Roma at that

time, historians have a hard time precisely pinpointing how many were killed, and some believe the total number of executions to be much higher, as high as 1.5000.000.

Despite the debates about the total death count, The Porajmos was a horrifying blow to the Roma community. In the years following the war, Roma rights organizations fought for recognition of their role in the Holocaust. They were left out of history for decades and did not receive reparations as the Jewish community did. It wasn’t until much later, in 1982, that Western Germany officially recognized that Nazi Germany had committed genocide against the Roma people.

Recognizing the Roma people’s role in the Holocaust has been a complex issue, both externally and internally, in the Roma community. Almost no records of the events survived from back then due to the tradition of oral history in the community and their nomadic lifestyle, which doesn’t allow one to own more than one can carry on her back or in the caravan. This promotes a view in the culture of moving forward, instead of being stuck in the past. And also makes it hard to document and, frankly, to remember. Adding to the complexity is the fact that many Roma would rather forget it all together instead of fighting for remembrance.

Because of the Roma history of being persecuted and stigmatized almost constantly through the centuries, the Roma has developed an ideal of moving on from the horrors inflicted upon them. Adam Bartosz describes it like this:

“The Roma are not a people that keeps alive the horrible memories of their past, they cannot live with that kind of nostalgia. They cannot take it with them.”

Instead of the moniker “never forget”, often associated with Jewish communities who also were victims of genocide by the Nazi Regime, the Roma version seems to be “forget and, move on”

The paradox of this ideal is that no matter how far you go, you cannot outrun the trauma of the Porajmos, Adam Batosz adds, acknowledging this contradiction.

Another way is through the visual medium of physical memorial sites dedicated to the lives lost during the genocide, which have been established all over Europe since the war. The most famous one is located in the Tier Garten in Berlin.

“The Memorial to the Sinti and Roma Victims of National Socialism” was designed by Israeli sculptor Dani Karavan and officially opened in 2012, 30 years after the German state recognized the Roma people’s part in the Holocaust. The monument consists of a dark, circular shallow pool of water surrounded by a path of flat stones, some with the names of concentration camps carved into them. Along the bronze rim of the pool, the poem “Auschwitz” by the Roma poet Santino Spinelli is featured. In the middle of the pool lies a triangular stone, referencing the triangle badges worn by concentration camp prisoners.

Going against the old Roma idea of moving on, one of the ways the Roma have been trying to deal with the trauma is through memorial sites and remembrance events, such as “The International Caravan of Roma Remembrance.” Starting at the Muzeum Etnograficzne w Tarnowie, several traditional Roma caravans begin a journey to sites in Poland where Roma people were mass-murdered during the war as a way of paying them respect. And also, along the way, celebrate Roma culture and traditions, like singing, dancing, and eating communally.

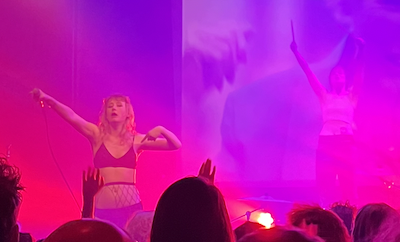

The ERIAC headquarters is located in Berlin, Germany. The headquarters also contains a gallery featuring artworks from contemporary Roma artists. The exhibitions change approximately 2-3 times a year and have a slightly different focus each time but are always by Roma artists.

“With this exhibition we tried to make it as multinational as possible, including artist from Russia, the US, Lithuania, Hungary and Romania. We also wanted to show the many different aspects of art being produced by Roma artist right now, so we have both paintings, ceramic sculptures, metal sculptures and also acrylic reliefs and video artworks”, project coordinator Joanna Wojtarowicz, explained.

One of the featured artists is the Hungarian artist Roland Korponovics, who lives and works in Budapest. Korponovics works in several mediums, with his primary art forms being performance and video. His work often deals with the different layers of identity modern humans divide themselves in and how these are represented in society. He explores parts of his own identity, such as heritage, sexual orientation, and social class, often critical of the postcolonial view of society in the Western world. In the exhibition, he is featured in the video artwork “Seatbelt” from 2017.

“My Roma origin has always been the starting point not only for the way I practice my art, but also for the way I see the world around me. I would call it a rather complex experience that cannot be separated from other elements that define my identity, such as my class and sexual identity. These three intersecting elements build a kind of stage for my themes, which flourish through my artistic practice.”

“Seatbelt” 2017, by Rolan Korponovics, courtesy of ERIAC, shot by Jester Van Schuylenburch.Korponovics is very appreciative of the opportunity to be featured at ERIAC as well as the work they are doing in providing a spotlight on Roma Artists in a broader context:

“I think that ERIAC is doing a great and complementary job, not only in making Roma artists visible, but also in working towards making a statement about the stereotypes that weaken the true understanding of Roma art and Roma communities. It also fills a gap in terms of challenging white, elitist and outdated positions in the Western art historical narrative.”

When it comes to the question about the lack of a tradition for visual art in the Roma community in the past, Korponovics views this also in the context of social class:

“It is true in the sense that visual art was always the privilege of a wealthier class until the 19th century, regardless of origin. Painting, for example – which has a long tradition in Roma art and is often labelled naive in the Western art historical narrative – has always been culturally dependent on

free time, availability of materials, and the possibility of expanding one’s perspective. In short: money.”

He argues that, especially when being a minority, it is essential not to try and interpret yourself from one point of view but rather to view yourself and the world around you from different perspectives and contexts.

“This also affects artistic practice, which I think has always been a root element of Roma art. It’s very conscious of who the work is addressed to, whether its subject matter is very personal or whether it speaks to a more general concept.”

Since ERIAC’s establishment in 2017, it has grown a lot. They have been given multiple grants, such as by other culture institutions to help them continue their work. Like creating or being part of events and exhibitions all over Europe and launching several projects to spread awareness of the struggles that the Roma people have faced and still face today. As well providing artist residencies to Roma artist in cities like Berlin, Florence and Budapest. And maybe most importantly, highlighting the many incredibly talented artists who work to represent their community and redefine what it means to be Roma in the world of today. Roland Korponovics, for one, is optimistic about what the future will bring:

“All of these together are increasingly helping today’s Roma artists become more aware of the use of mediums in their creative processes, leading to more and more great Roma conceptual works.”